The social model: do we disable people through our tech?

Do our society’s design and tech choices actually cause disabilities? In this article, we honor Mike Oliver, discover the origins of the social model and dive deep into the role that we in tech play in perpetuating ableism.

Claudio Luis Vera

Feb 01, 2022

Content warning: this article includes topics that may be difficult for some readers like eugenics and poster children.

This February, Stark will be spotlighting the social model of disability, which was a groundbreaking idea when it was first introduced in 1976. In the social model, people are disabled by the barriers society creates, not by their physical impairments or differences.

The term “social model” is widely credited to Mike Oliver, a prominent figure in the British disability movement who brought it into mainstream thinking.

Mike Oliver (1945-2019) became a lifelong wheelchair user after a teenage swimming accident in 1962. After a year of rehabilitation, he taught adult education at a juvenile prison, then pursued a degree in sociology, which led him to a doctorate in 1978. Oliver published Social Work with Disabled People in 1983, which introduced the concept of the social model to the general public. Over the next few decades, his books became the foundation for the field of disability studies at the University of Kent in the UK and elsewhere.

Stark honors Mike Oliver on his birthday February 3 with a series of articles and events on society and disability. His legacy lives on in the content and teaching materials we produce, where we treat the social model as a core principle.

Perhaps the best biography for Mike Oliver is his obituary in the Guardian published after his death in March 2019. To get a better appreciation for Mike Oliver, you can also watch an Interview with him from Kent University.

The effect of our society's design and tech choices

Until recently, designers, developers, and company leaders would never consider the needs of anyone who weren’t as abled as themselves.

I know. I was one of those inconsiderate people.

My own career in digital began in the early 1990s when digital platforms like the World Wide Web first came about. In those days, we built content and apps quite literally for people like us, for like-minded and similarly-abled members of the tech elite, the digerati. When AOL and others expanded use of the Internet to include a border population, many of us early adopters acted like hipsters, feeling contempt for the new, the less tech-literate, and the less-abled.

In the 30-odd years since our society’s values have become so much more inclusive. It’s become an accepted fact that design and technology must meet the needs of 100% of the population, not just people like us. Still, that attitude of exclusion from the 90s persists to this day as cultural baggage.

But the roots of ableism — the devaluing of disabled people — go much further back than the early Internet.

Origins of the social model

For most of history, our society has favored the fit and able in its choices for tools and construction. Stairs and platforms are a common feature in traditional architecture, and some entire settlements, like the Puebloan cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde required ladders to get around. If someone was incapable of navigating the built environment, it was always seen as being the individual’s problem — and never as an issue with the choices in construction.

In the 1970s, disability activists in the UK began to move away from the traditional view of the individual being deficient. It was a huge shift, comparable to Copernicus’ realizing that the Earth revolved around the Sun. This new worldview was first put into writing by the Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS):

"In our view, it is society which disables physically impaired people. Disability is something imposed on top of our impairments, by the way we are unnecessarily isolated and excluded from full participation in society. Disabled people are therefore an oppressed group in society." Fundamental Principles of Disability, UPIAS pamphlet (1976)

A few years later, this thinking was named “the social model of disability” by the renowned activist and sociologist Mike Oliver in his book Social Work with Disabled People (1983). In that book, Oliver sought to explain the source of disability, as to whether it came from the individual’s physical abilities (the “individual model”) or from society (the “social model”).

The social model has profound implications for those of us who build products, even more so in the digital world. Our everyday design and technology choices carry a deep impact on those who use our products. They can be small everyday choices, like remembering to add captions when posting video content, or alternative text when posting images. Quite often, these smaller decisions can increasingly be checked through automated tools.

But other choices are more strategic and can’t be checked by bots, like whether a new social audio app should have captions to include deaf or hard-of-hearing users. Should the makers of a gaming console require two hands to use it? …or should it be played with one or no hands, for example?

Both examples speak to the huge responsibility carried by those of us who work in professions that design, create, and build the objects and environment around us. Perhaps the real question is:

“How many people does the design of our product or service disable?” —Gareth Ford Williams, 2022

How did we get here?

Ableism is actually the flip side of many of the values that our culture holds dear. We place enormous value on productivity and efficiency, and we’ve built an entire business culture around it. We cherish independence and self-sufficiency, even though it’s not a sustainable goal for much of a person's lifetime. And society shows its dark side for those who don’t meet the standards of productivity and self-sufficiency.

Industrial Man

Productivity is central to our society—whether in the economic sense or the fulfillment that comes with the fruitful use of your time. It’s hard-coded into most industrialized cultures as a virtue, and your ability to be productive is a powerful indicator of your social worth.

In the industrial-age family, the adults (typically male) are the breadwinners — those who exchange work for wages that provide the household’s sustenance. A breadwinner’s value can be seen in a court case involving death or disability. Typically, a legal settlement is based on the number of years of wages that the plaintiff will have lost.

Our view of productivity is also patriarchal: it gives little or no value to the mostly female population involved in care work: childcare, or tending for the aged and disabled. In fact, it can be the source of additional bias: a mother of young children is often seen as less productive in the workplace, even when the children are in full-time daycare. Most economic data, such as gross domestic product, don’t even figure the billions of person-years of labor that go into the care economy every year. Even though all of us are dependent on others at some point in our lives — in childhood, extreme old age, or recovery — we expect ourselves to be fully self-sufficient, both physically and economically.

In libertarian thought, the phrase “makers and takers” frames an extreme form of this philosophy. Makers are those who generate economic income; takers are everyone else, including those who may need some sort of assistance.

By definition, the cult of productivity favors the quick over the slow, the abled over the disabled. As we age and acquire impairments, most of us do slow down physically. For people with severe impairments, common tasks take even longer, often referred to as “being on crip time” by disabled people. Being “slow” comes with its own set of social stigmas, not the least of which is a slur for cognitive disability.

The cult of normality

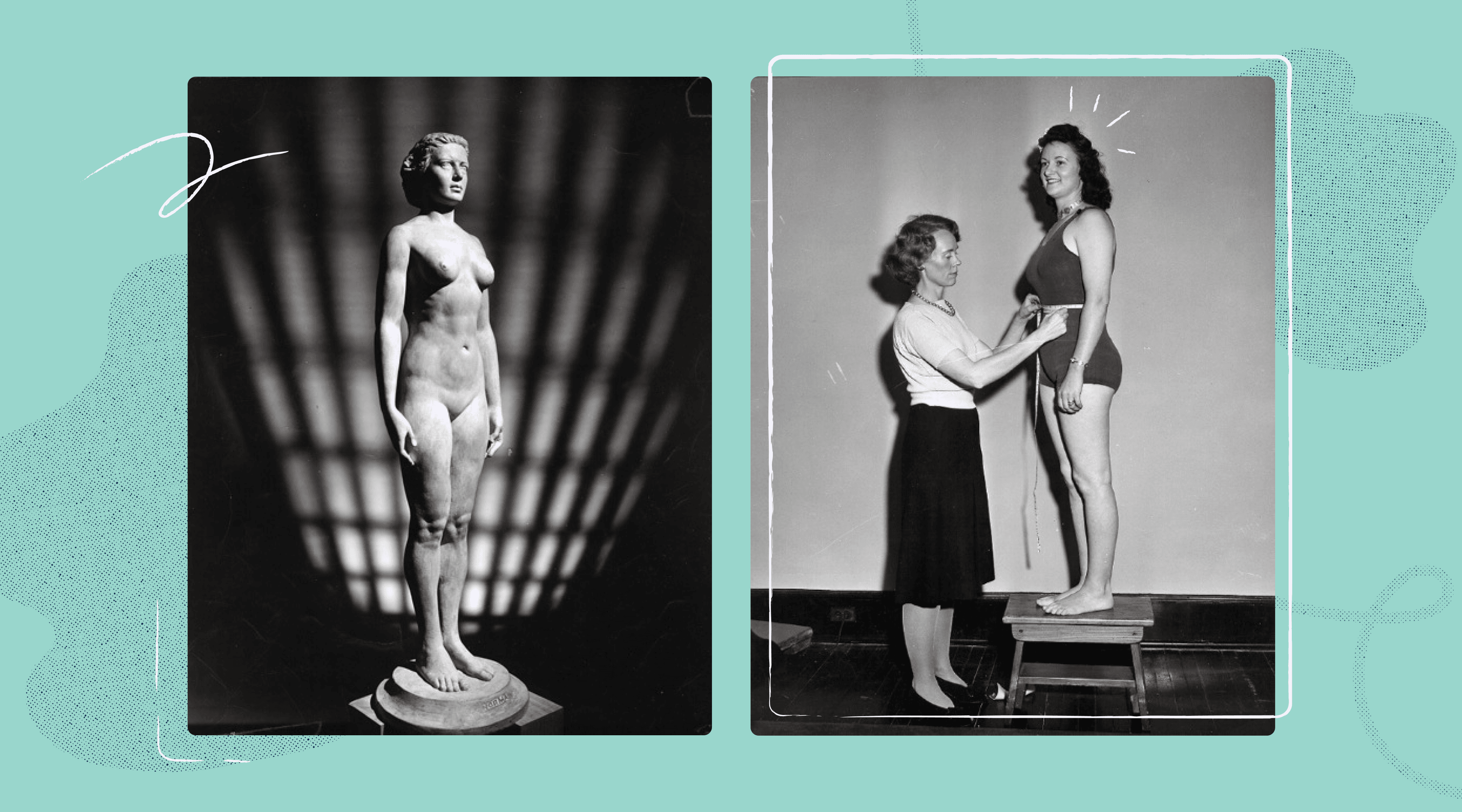

Starting in the Enlightenment, a pseudoscience developed around determining what makes up normal. People were measured exhaustively with calipers, scales, and every other imaginable device in an effort to find the proportions of the ideal human. The word “normal” came to describe whatever was close to the average in proportions and abilities. In Ohio, a statue was commissioned for the Cleveland Health Museum of Norma, an idealized woman whose proportions were derived from the size data of 15,000 young adult women.

No single human ever matched all of those proportions exactly. Another study was conducted on 4,000 airmen at the Wright Air Force Base, where they were measured on 140 size dimensions to determine measurements for the ideal cockpit. As with Norma, even the most ideal subjects never matched more than a small handful of the dimensions.

At its peak in the 1920s and 1930s, the cult of normality went hand-in-hand with nationalism and a quest for genetic purity. Eugenics, as it came to be known, was the quest to improve future generations by weeding out undesirable traits. For people with disabilities or other conditions that didn’t meet the “norm”, eugenics could mean forced sterilization or getting put into an institution.

The medical model and the medicalization of disability

In this wave of pseudoscience, whatever deviated from the idealized norm would be given the scientific-sounding labels of “abnormal”, “deviant”, or “aberrant”. Those who deviated enough were seen to be suffering from a variety of disorders, deficiencies, or defects. These were considered to be medical conditions that often required the intervention to correct those deviations through drugs, surgery, or institutionalization.

To Mike Oliver and the early disability activists, the very language of medicine towards disability was “divorced from the direct experience of people with impairments”. In his writing, he referred to the “medicalization of disability” in which entire lifestyles were reduced to jargony medical conditions. This was the basis of what he called the individual model, and what most of us today refer to as the medical model.

The medical model has a few built-in flaws. First, it looks at disability exclusively as a medical condition to be treated through a procedure or drugs. It offers little in the way of long-term adaptation or help with a person’s lifestyle, let alone acceptance into society. In the medical model, having a disability is based on a binary have-it / don’t-have-it diagnosis by a physician, which implies affordability and access to healthcare. A medical diagnosis is almost always a requirement for receiving disability benefits, insurance coverage, and assistive technology.

Poster children and the charity model

Mike Oliver and other disability activists battled another worldview that persists to this day: the charity model — in which people with impairments are helpless and to be pitied. This view became especially popular with corporatized philanthropy for specific disabilities, and one longstanding example was the Jerry Lewis Telethon.

For 40 years in the US, the Muscular Dystrophy Association would broadcast a 24 hour marathon fundraiser on Labor Day weekend. This telethon would be a maudlin affair, with the host Jerry Lewis alternately mugging for the camera and shedding tears while holding cute young disabled children, popularly known as Jerry's Kids. At one moment in the 1973 broadcast, Lewis explained the telethon’s mission as “God goofed, and it's up to us to correct His mistakes.” Still, viewers would be moved to open up the pocketbooks and mail checks in to the charity, ostensibly to fund research toward a cure for muscular dystrophy.

Activists and members of the disability community loathed the show and its host. It perpetuated the stereotypes of people rendered helpless by a medical condition, and never worked toward improving mobility, independence, or autonomy for the disabled. In the words of one Jerry’s-Kid-turned-activist Mike Ervin, what’s needed is, “accessible public transportation and housing, employment opportunities and other civil rights that a democratic society should ensure for all its citizens.”

Going beyond the medical model in design

In design, the medical model has had a far larger impact than most would imagine. Most designers imagine assistive technology and prosthetic devices as forms of medical equipment and design them merely to provide a solution to a medical problem. A typical hospital wheelchair or an elder’s walker at a nursing home are examples of the soullessness of this type of design.

On the other hand, mainstream consumer products are designed to have a number of what we could call Marie Kondo attributes to them: they should be beautiful, they should spark joy, and they should have some sort of significance that makes a statement about the owner.

For the past few years, there has been a trend in prosthetics away from the fake flesh-toned simulacrums of yesterday toward plastic 3-D printed limbs. The aesthetic of the limbs is more that of a cyborg or a Transformer, and they’ve become especially popular with children. The wearers are seen as cool by their peers, as opposed to being bullied or pitied for having a medical condition.

The tipping point

In my own career, I’ve seen a progression from the snotty digital elitism of the 90s to a more inclusive worldview in the 2020s. While a few of the issues that Mike Oliver pointed out have been resolved, there has been some progress. New assistive technologies have sprung up, while new forms of exclusion appear in tech.

To read a magazine in the 1990s, a blind person would need to wait for the Braille edition of a magazine to be delivered to the local library or they’d have to recruit a sighted friend or neighbor to read it for them. While the internet and screen readers brought availability of content and some autonomy, sighted site builders typically neglect to make sites compatible with assistive technology. Or entrepreneurs launch new platforms that categorically exclude an entire class of disabled people. As issues are resolved, new issues spring up. And as awareness of accessibility grows, we’re at or near that tipping point where issues begin to be resolved faster than they’re created.

For example, in The New Politics of Disablement (1990), Mike Oliver expressed his doubts about the viability of the disability movement within capitalism. After enduring the social callousness of the Thatcher years in the UK, Oliver felt that the disability movement had been co-opted by corporate interests and become ‘disabling corporatism’. Corporatized charities for disability still endure, but they’ve become less focused on a medical cure.

As for capitalism? As a venture-funded startup, we at Stark hope to prove him wrong, that disability inclusion is entirely possible within the business environment of the 2020s.

In our next post, we’ll look at how digital innovators can tip the balance and bring about a more accessible society. We’ll dive into ways to re-calibrate the design and development process at a critical point to introduce accessibility.

A recovering designer, Claudio is an accomplished creative director and studio principal with a background in digital that goes back to the early 90s. Claudio’s worked with a variety of clients ranging from Harvard University and the MIT Media Lab to Intelsat and many tech startups.

Want to join a community of other designers, developers, and product managers to share, learn, and talk shop around all things accessibility? Join our Slack community, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.